by Luke Alfred - Jun 08, 2024

No race captured the hype of the 2000 Sydney Olympics quite like the men’s 4x100 freestyle relay. The reasons for such heightened expectation were rooted partly in history, and partly in the tabloid inclinations of the press. The event was introduced for the first time at the 1964 Tokyo Olympics and, since its inception, the USA had unerringly won it. Nine gold medals later, their swagger was effortless, their crown assumed: they were undisputed kings of the pool.

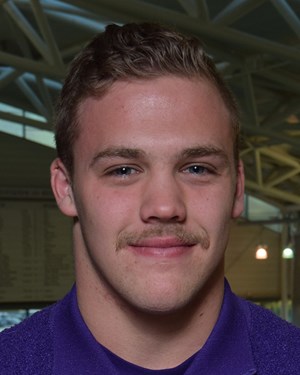

Gary Hall Jnr, a vital member of their team, was their praise-singer in Sydney. He was fond of shooting his mouth off, reminding the world in general but the Australians in particular of the US’s manifest destiny in the event. The Cincinnati-born Hall was the quintessential showboater. In his stars- ’n-stripes robe, he would shadow box on the pool deck; sometimes he’d play air guitar or indulge in mock World Wrestling Federation moves and manoeuvres. Some loved him, arguing that he brought a much-needed touch of showmanship to the sport. Others weren’t so sure.

The Aussies, with the sublime Ian Thorpe and the explosive Michael Klim in their ranks, observed Hall’s antics and shook their heads. Sydney was their home patch, a city immersed in Australian swimming folklore. The peerless technician, Murray Rose, had swum as a boy in the Manly saltwater pool in the 1950s. He also went swimming in Sydney Harbour, likening his Christmas swims when the massive ‘King’ tides rolled in from the Pacific, to an ‘adventure into a different world’.

Dawn Fraser, the larrikin eighth child of a working-class Balmain family of Scottish immigrants, was another Sydney swimming legend. She won gold medals in the women’s 100-metres freestyle in three – Melbourne, Rome and Tokyo – consecutive Olympics. In coming to Sydney, the US were entering the waters of an Australian swimming temple. The Aussie sprint relay four were disinclined to allow the Yanks to extend their record in their backyard.

Hall cranked up the volume still further when, shortly before the final, he wrote on his blog: ‘My biased opinion says that we will smash them [the Australians] like guitars. ’It was a metaphor lacking in requisite lightness. At 6 foot 6 inches tall and with a quiff to make any Country-and-Western star proud, Hall was a power swimmer, not Ted Hughes. He would show those upstart Aussies in the pool.

As luck would have it, Hall swam the fourth leg of the relay final against Australia’s Thorpe, taking a narrow lead into the final 50 metres as it became a two-way race for gold between the reigning champions and the Olympic hosts. With 20 metres left, Hall was still narrowly in the lead. As Hall and Thorpe approached the line, Thorpe reeled in the American with literally his last two strokes, touching the wall first. In the pandemonium of the Australian’ celebration, Klim, who had swum a world-record time in the first leg for Australia, strummed a few bars on his air guitar.

In the euphoria and excitement, few cared to remember that in his blog Hall had struck a note – as it were – of uncharacteristic ambiguity. In the line following his infamous ‘guitars’ quip, he had written: ‘Historically the US has always risen to the occasion. But the logic in that remote area of my brain says it won’t be so easy for the US to dominate the waters this time.’

Such a close reading of the event and the brouhaha surrounding it was beyond pretty much everyone, including the South Africans. They bombed in the 4x100 freestyle relay, finishing fifth (behind Australia, Russia, Sweden and France) in heat two of the first round. Their swimmers won only two medals in the Sydney pool (Terence Parkin, sandwiched between two Italians, grabbing silver in the 200-metre breaststroke; Penny Heyns winning bronze in the 100-metres breaststroke women’s final) returning home chastened and demoralised.

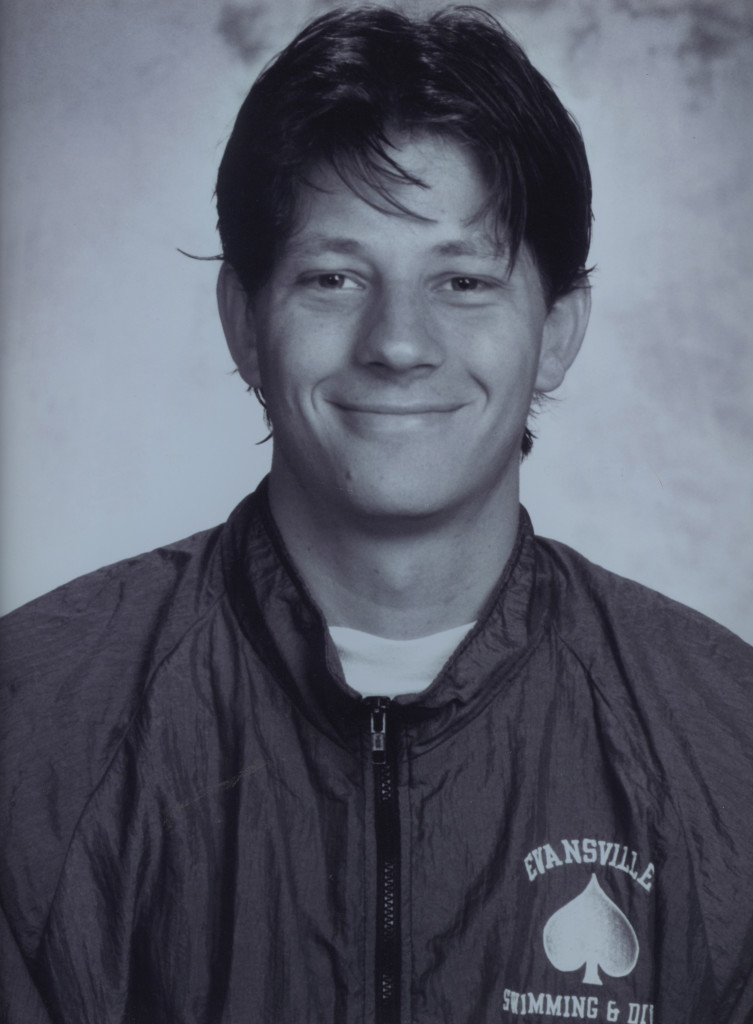

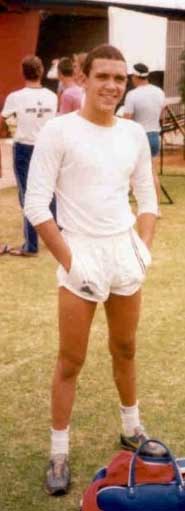

Two of their number, the highly regarded Ryk Neethling and up-and-coming gunslinger, Roland Schoeman, had an Olympics to forget. Only 20 years old, Schoeman hadn’t made the final in either of his favoured short-distance sprint events, while the older Neethling finished fifth in the 1500-metres free and eighth in the 400-metres freestyle final. ‘I talked the talk,’ he recalls. ‘I went to Sydney ranked in the top three in the world in three events – the 1500 metres, 400 metres and 200 metres – and didn’t medal.

‘On the plane [out of Sydney] I read a book called Positive by an Australian discus thrower and shot putter [Werner Reiterer] about the systematic world of doping, which wasn’t great for my mental state. The [Sunday Times] journalist David Isaacson said I “choked” and I let it get to me. I came back and thought, “Fuck it, I’m done.”’

So shattered was Neethling by the Sydney experience that he didn’t swim competitively for nearly two years. He had arrived at the University of Arizona on a scholarship after his first Olympics in Atlanta in 1996, and now the university’s home in Tucson was a sanctuary. He was far from Sydney, far from his failures and thousands of handy kilometres away from the accusing gaze of the South African media. He became anonymous again and vanished into a bubble of disappointment and self-pity.

After his working day handling sales and leasing as a Tucson commercial real-estate broker was over, he sometimes headed for a local heated pool for a few easy recreational lengths. He played and frolicked, searching for what he’d lost in the Sydney trauma. He did a little low-key Masters coaching from six to seven in the evenings. Watching others older and less talented than himself was a balm. His Masters classes always seemed to enjoy themselves; they splashed about and had fun. They yelled. Neethling watched it all and was reminded of water’s ability to console and heal. ‘It gave me a different perspective. I gave them some pretty challenging exercises and they just gave it horns. These old people would just attack it.

‘For me, the fun inside the pool took a little bit longer to arrive.’

The son of a prominent Bloemfontein attorney, Neethling was a middle child enveloped by two sisters. He stuttered badly as a child and his biographer, Clinton van der Berg, surmises that although he survived a drowning incident in the family pool as a five-year-old, water was always ‘a refuge’ of silence and peace.

Born in 1977, Neethling remembers Zola Budd ‘running past the house’ and her subsequent exploits competing for Great Britain in the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics. Those Olympics were subsequently immortalised by Bud Greenspan in his American-made documentary called 16 Days of Glory, a boosterish yarn purporting to tell the inside story of the Games.

Neethling watched the film as a boy, transfixed in front of the screen: the march-past, the pageantry, the stellar performances of Carl Lewis. Nearly 30 years later he can still recall seeing the men’s 200-metres butterfly final, billed as an epic race between the Cuban-born young American, Pablo Morales, and the German Michael Gross, nicknamed The Albatross.

The two were neck and neck with 20 metres to go, the slightly less experienced Morales making a technical error that allowed The Albatross to reach out a lanky arm and grab gold. ‘I watched it in Bloemfontein on my own, when I was perhaps 12 years old,’ says Neethling. ‘I saw the Coliseum and the crowds and all those things just blew my mind – I realised that was what I wanted.’

When he graduated from the University of Arizona in May 2001, Neethling found himself at a loose end. He suddenly had no formal swimming obligations. Occasionally he’d find himself on the deck, jumping into the pool and casually ' doing a little damage’. This aside, he was left to his own devices. There were no college meets, no pressure, no practice routine. ‘No coach said, “Hey, Ryk, you’ve still got it, buddy. Come and join us.” I was just there, sort of trying to decide on my future.’

Through the latter half of 2001, he slowly realised that he had unfinished business with both his talent and the sport. If he didn’t start to swim competitively again he would forever be remembered as the precocious wannabe who bombed in Sydney, his vanity such that he never returned. He got his shit together and bulked up in the gym, putting on 15 kilograms, transforming himself from a distance swimmer into a sprinter.

His development was halting; physically, he might have changed shape but psychologically he was lost in soggy self-regard. ‘I wasn’t always the best person to be around,’ he said. ‘Relationships suffered.’ Slowly, the water began to restore him. He found equilibrium and a semblance of calm. ‘I couldn’t look myself in the mirror while shaving in the morning. I didn’t want to be a “what if?” guy.’

With Neethling on the team, the South Africans arrived in Manchester for the Commonwealth Games in July 2002 harbouring no great hopes. Schoeman and Lyndon Ferns joined Neethling to form the backbone of the freestyle relay team, with the fourth place being filled by Hendrik Odendaal. In the event, the South Africans grabbed silver, two and a half seconds behind the Australians but a handy half-second ahead of the bronze-medal Canadians. Ferns has no particular recollection of the event but mentions that, looking back, at least what was to become the Olympic relay team had made a cautious beginning.

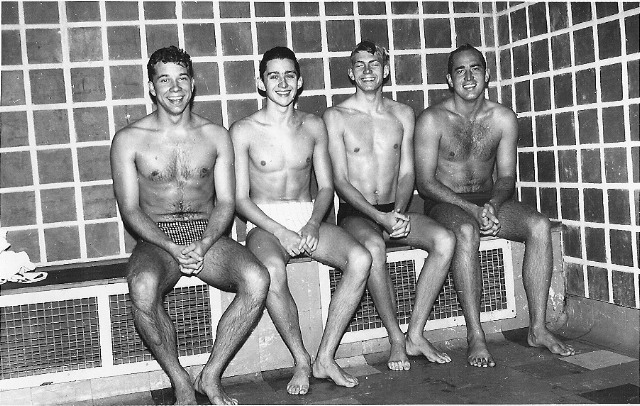

Six months later and Ferns had formally enrolled at the University of Arizona. He, Schoeman and Neethling now lived in the same city. They trained together and all revered and trusted the college swim coaches, Frank Busch and Rick DeMont. The 2004 Olympics were a mere 18 months away.

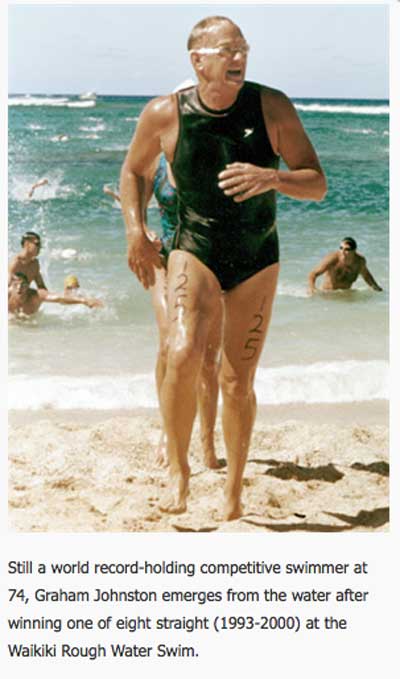

DeMont had his own Olympic story. As a naturally graceful young California swimmer, he won gold in the 400-metres freestyle event at the Munich Olympics in 1972 only for the medal to be snatched away when traces of a banned substance were revealed in his asthma medication. He was subsequently scratched from the 1500 metres (in which he held the world record) and returned to the States angry and confused. An intelligent child (he skipped a grade), he’d made the American authorities aware of his medication in the pre-Olympic paperwork all athletes were required to complete. The problem was, the Americans had somehow failed to alert the IOC who were in no mood (these were the early days of doping and anti-doping legislation) to turn a blind eye or admit culpability.

After months of introspection, DeMont returned at the World Aquatic Champs in Belgrade a year later, where he became the first swimmer to puncture the four-minute barrier in the 400-metres freestyle. After Belgrade, at the tender age of 17, he retired from competitive international swimming forever.

In later life, DeMont, an artist in both watercolour and oils, moved from California to Arizona, where he started a long-standing relationship with the Arizona Wildcats, the college swim team. ‘I definitely come at it [coaching] from a creative point of view,’ he has said. ‘Building a dance – you know, swimming’s nothing but a dance – you learn how to dance and you’ll be fast.’

Both Busch and DeMont stepped in when Neethling, Schoeman and Ferns returned to campus in the summer of 2003, having finished eighth in the final of the 4x100 freestyle relay in the World Aquatics Championships in Barcelona in July. The South Africans only made the final because the Swedes had been disqualified on a technicality in their heats. The reprieve, though, was temporary. ‘If we stopped halfway through,’ says Neethling, ‘no one would have missed us.’

Busch’s office on campus a week later ended up being the venue for one of the more important meetings in South African swimming history. As the three sat in front of probably the most illustrious coach in US swimming history, they felt like guilty schoolboys before the headmaster. The impression wasn’t helped by DeMont, standing nearby. He was generally jocular, full of goofy ease in a T-shirt, cargo shorts and a peaked cap. Now his arms were folded.

‘You guys are better than eighth,’ began the grizzled Busch gently.

‘Shit happens coach,’ shrugged Schoeman.

‘Look, guys, you’re on the cusp of something special. You’ve got to start investing in each other. You can’t swim as individuals. Not any more. Not on a relay team.’

Silence.

‘If you come together now you’ll do something that will be remembered in South Africa for a very long time. Something special.’

‘You’ve never even been to South Africa, Frank,’ said Schoeman.

Mild laughter.

‘I know that South Africans are crazy about their sport. There: Francois Pienaar!’

More laughter.

‘If I can just come in here. You have three prongs now, guys; just take the leap of faith. There’s an Olympic medal here for the taking,’ offered DeMont. ‘Couldn’t have put it better myself.’

After the debrief in Busch’s office, the parties didn’t dive immediately into the circle of love. Neethling and Schoeman had always had an itchy relationship. Schoeman was more tolerant of the South African national coach, a German by the name of Dirk Lange, than was Neethling. And Neethling always felt that Schoeman was wary of his territory when he made the transition, post-Sydney, to the shorter, more explosive sprinting events.

Over time, relations thawed. Although the team was still looking for an elusive fourth member, the parties began to trust one another. According to Neethling, they egged each other on at the gym and supported each other in the pool. They became collectively accountable and even began to enjoy each other’s company. ‘We reminded each other of how we felt when we got last place at that World Championship,’ said Neethling. ‘Before a workout would start, or towards the end, we would say, “Just remember how we felt in Barcelona. ”So we used that as a springboard. We stopped making excuses. And, ja, we just invested in each other. We formed this brotherhood.’

During the World Cup in Durban in early December 2003, Neethling and Schoeman were thrilled to find out that Ferns had swum sub-50 seconds for the University of Arizona in the 100-metres at a meet in Austin, Texas. Things were clearly taking shape, Ferns’ time of 48.99 giving them hope that their efforts since the conversation in Busch’s office were paying dividends. ‘That was the Texas Invitational, if I remember – the first qualifying event for the Olympics,’ says Ferns. ‘I’d just started my second year at Arizona. We did a long course in the evening and I was feeling good. I just went out and swam.’

After the World Cup, Neethling returned to Bloemfontein for the December holidays. He worried his mother, San-Marié, because he was picky about her cooking and baking. During Christmas lunch he showed restraint, only breaking his resolve for dessert. San-Marié was hurt, and asked why he wasn’t eating more. Neethling explained his need to put the haunting of Sydney behind him. He’d swum 15 kilometres on Christmas Eve in the local Virgin Active, he explained, and after Christmas lunch, he was about to head for the municipal pool to swim a further 15 kilometres. Bloemfontein was almost eerily deserted that afternoon because people were holidaying on the coast. The sidewalks were empty, the roads free of traffic. In the searing afternoon heat, he swum length after length in the great emptiness. This was his therapy.

Despite his spellbinding swim in Austin, though, Ferns was suffering. He trained too hard as 2003 segued into 2004 and felt burnt out. But he took a deep breath, found reserves of strength he didn’t know he had, and looked forward to the upcoming Olympics, now only months away.

Swimming with Neethling and Schoeman at the Janet Evans Invitational at Long Beach, California, on 11 June, Ferns helped the University of Arizona to first place. It was not an all-South African team (the fourth spot was taken by a local Arizona swimmer, Mark Warkentin) but the result affirmed that the relay team was on the right track. In swimming 3.22.00, they beat Venezuela and Australia (with Klim in their line-up) into second and third place respectively. ‘After that we spoke about times quite a lot – and how Lyndon’s 48.99 was going to fit in,’ said Neethling. ‘We also decided that whoever was going to be the fourth member of the relay squad [in the Olympics] would swim third.’

In the Athens Olympic village Neethling found himself sharing a room with Parkin, the Sydney silver medallist. Parkin had a cold and was coughing terribly, retching great gobs of phlegm into a bottle he kept on his bedside table. ‘There was no issue – Terence and I have known each other for a long time – but he’s deaf,’ said Neethling, ‘so he had no idea of the noise he was making. I asked to be moved. I was paired with a sailor, but he was on the water, and I didn’t see him for a week.’

The subject of roommates aside, the opening days at Athens were less than optimal. Swimming South Africa (SSA) had negotiated a sponsorship contract with Speedo, while the relay swimmers favoured the Arena swimsuit and Nike’s cap. There were angry words, much to-ing and fro-ing, with the parties resolving that if the relay team were to be fined, it was to be done after the Olympics.

An already tense relationship between swimmers and administrators was plunged closer to crisis on the subject of DeMont (Busch was honouring his commitments as head coach of the US Olympic team). The University of Arizona swimmers argued that they wanted DeMont on the pool deck, with SSA responding by saying they’d used up their accreditation: which had gone to official coach Lange. ‘Rick ended up becoming an honorary Venezuelan – it was all we could get accreditation-wise. He was a hour- a-half-drive away from the deck. Still, he was there and that was important for all of us,’ said Neethling.

One matter still needed to be decided: the fourth member in the relay team. A couple of days before the official start of the Games, there was a swim-off. Darian Townsend dipped beneath 50 seconds for the 100-metres free, while Karl Thaning and Eugene Botes couldn’t broach the 50-second barrier. Townsend was a shoo-in; the team now had their fourth man. Through trial and error, they had agreed upon an order since the forgettable efforts of Barcelona in which the order was Townsend, Schoeman, Ferns and Neethling.

In the revised line-up, Schoeman would now lead off in an attempt to secure an early lead; Ferns, recovered from his bout of over-training, would follow; after that, the new man, Townsend, would hopefully protect the by-now established lead. Townsend would hand over to the anchor Neethling, who was expecting to swim against the United States’s Michael Phelps.

The race order worked to perfection, South Africa winning her heat on the Sunday morning in close to a world-record time. They were over the moon, but wise enough to reel in their instinct for windgat self-promotion. According to Neethling, they politely eschewed media interviews. They tried to be as calm and as natural as they could be. After their cool-off swim, DeMont gathered them round, a broad grin on his face.

‘Great swim,’ he said, rubbing his hands together as he stepped closer. ‘So, I’ve got a story for you ahead of tonight’s final. There are these two kudu bulls standing on top of a hill looking into a valley at a group of grazing cows, right? The young bull turns to the older one: “Let’s rush down and fuck the most beautiful cow,” he says. The old bull considers the young bull’s impetuosity gravely and shakes his horns. “No,” he says, “that’s not the way to do it. Let’s canter down and fuck them all.”’

It was difficult to relax in the athletes’ village. Neethling caught a fitful 15 minutes sleep. In an attempt to calm down, he listened to Juluka on his headphones. Ferns tried to distract himself. ‘It was more excitement than nerves, to be honest,’ he said. ‘We were there to win a medal – we knew after the morning heats that we’d be close. We all tried to relax but that was almost impossible.’

Neethling breathed deeply. ‘They always say that you must have butterflies,’ he said. ‘But the trick is to get them to fly in formation.’ At 6:30, after a restless afternoon, the team gathered in the dining hall. Neethling grabbed his usual: two Red Bulls and two bananas. Schoeman slid a chicken breast and a couple of rice balls onto his plate. As he forked a rice ball into his mouth he found he couldn’t swallow; his mouth was too dry. Specs of rice dribbled down his chin. The incident lowered both the tone and the tension.

When they recovered from their hysterics, the team had something to eat. Shortly after the team arrived at the main Olympic swimming venue they were approached by a frisky DeMont. He’d somehow been privy to the announcement of the US team (and their racing order) and was amazed to report that Hall – who had swum for the US relay team in the morning heats – had been benched.

As he circulated the news, the four swimmers couldn’t believe the Americans had chosen to swim in the order they had. Later it emerged that Ian Crocker, who swum second-fastest of the American four in the morning heats, was suffering from a sore throat, but the South Africans didn’t know that then. All they saw now was that Hall Jnr wasn’t part of the US team. It struck them as ludicrous that Crocker would go out first, followed by Phelps, Neil Walker and Jason Lezak. ‘We just couldn’t believe the order,’ said Neethling. ‘I visualised that [as anchor] I’d swim against Phelps – I’d been visualising it for months. We would never have gone out with Crocker; we’d have gone out strong with Walker and Lezak.’

In the event, Crocker touched the wall in eighth in the final after going out first for the States. Schoeman, swimming first for South Africa, achieved the much-talked-about good start and stormed to the lead, which he held throughout. Ferns, swimming second, swam the race of his life. He not only held onto Schoeman’s lead but possibly extended it slightly, leading from the Italians in second, with the Australians bunched in a group a couple of metres back.

Ferns had good reason to blaze. Hall was at his mouthy best between the heats and the finals when he announced within Ferns’ earshot that it was a pity he swam so well in the morning, because he wasn’t going to repeat it. ‘Hall was not alone for thinking that way – everyone said it,’ said Ferns, nonplussed. ‘Roland and Gary shared the same agent, David Arluck, and David was saying it too.’

After swimming a magnificent leg against Phelps, Ferns made way for Townsend. The last pick of the relay team (and the so-called soutie amidst the boertjies) helped to banish the ghosts of Barcelona. Racing third, Townsend swam magnificently; the South Africans were still in the lead when he handed over to Neethling, who had watched the first three legs with mounting tension. ‘With 10 seconds to go, I changed my strategy completely: I wanted the guys to see my foam,’ remembers Neethling. ‘I went out as fast as I could. At 70 metres, the pain started to come in. I felt as though I was swimming in syrup.’

Back home in Bloem, Neethling’s parents and sisters all watched the final in different rooms: San-Marié was in the bar, his sisters were in their respective bedrooms and Ryk Snr was in the television room. ‘After Roland’s leg, Dad roared like a lion – he’s a big man – so everyone came running. By the time Darian started his swim they were all in the TV room together. When we’d finished, the phone didn’t stop ringing for a week. The following morning the domestic workers in the suburb started an impromptu dance.’

Neethling held on in the last 30 metres as Lezak and Pieter van den Hoogenband of the Netherlands pushed him close, Van den Hoogenband pipping the Americans in the final few metres. Amidst wild jubilation, the gold medal was South Africa’s. In the best race of their lives, they had beaten the Australians’ world and Olympic record, set in Sydney four years before, by a hefty half-second.

The Americans finished third, condemning themselves to endless post-mortems about race orders, sore throats and Hall’s exclusion. The Australians, so full of bravado four years before, finished sixth. Pumped with adrenalin, Schoeman, the sprinter who had established the lead, compared the victory to the film, Any Given Sunday.‘As the movie says, “Any given Sunday. ”For the relay, I told the guys, this is our Sunday,’ said Schoeman emotionally.

How South Africa Swimmers Stole America's Olympic Gold

Luke Alfred - Jun 08, 2024

https://lukealfred.substack.com/p/how-south-africa-swimmers-stole-americas