Disabled Swimming

Disabled Swimming

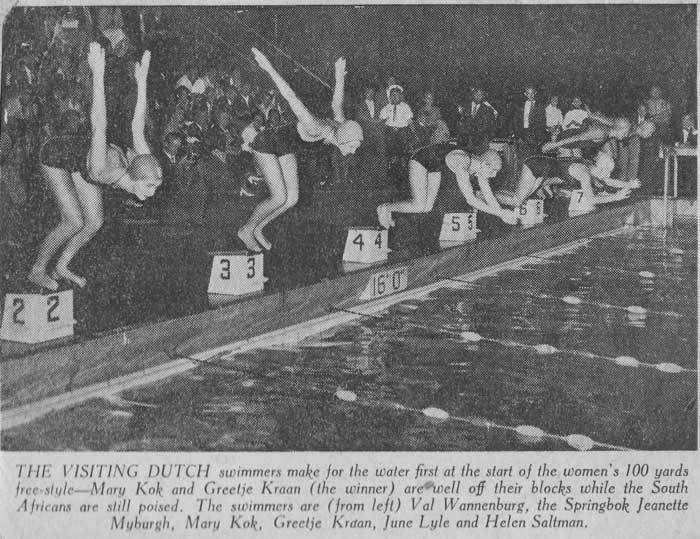

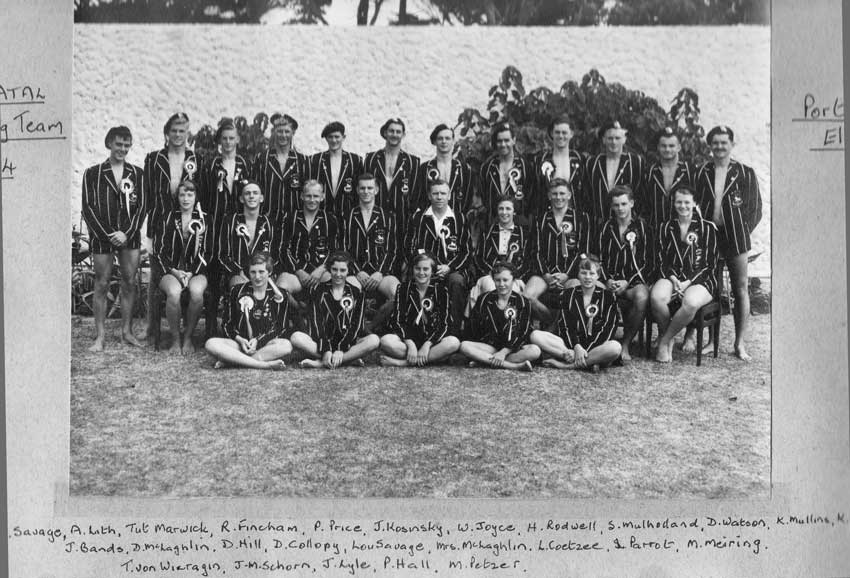

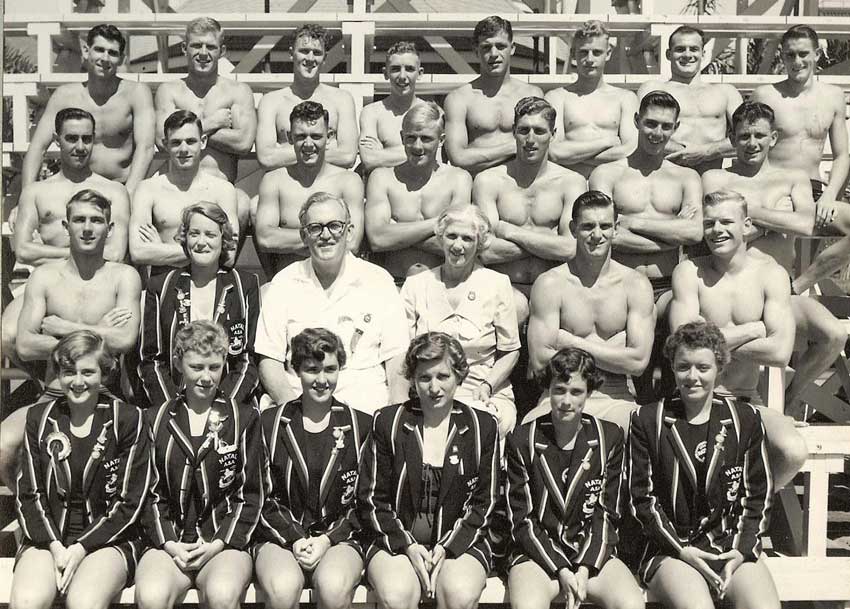

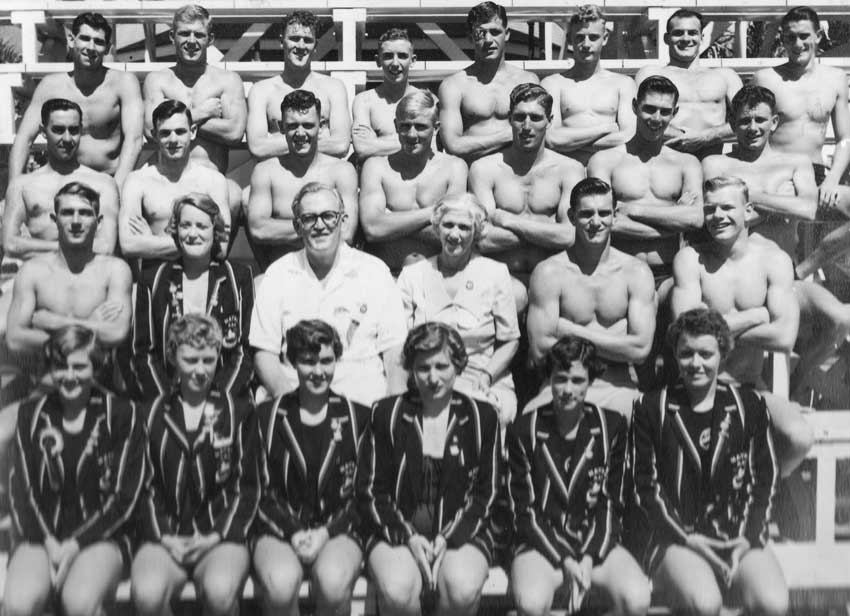

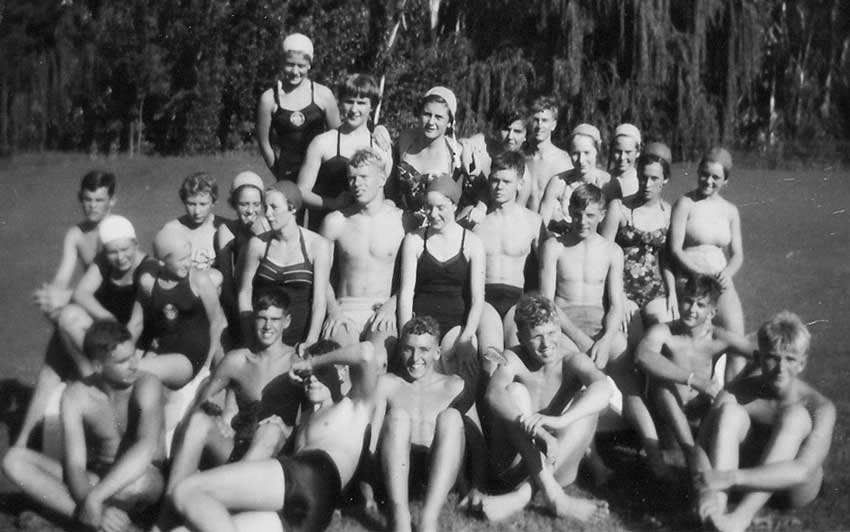

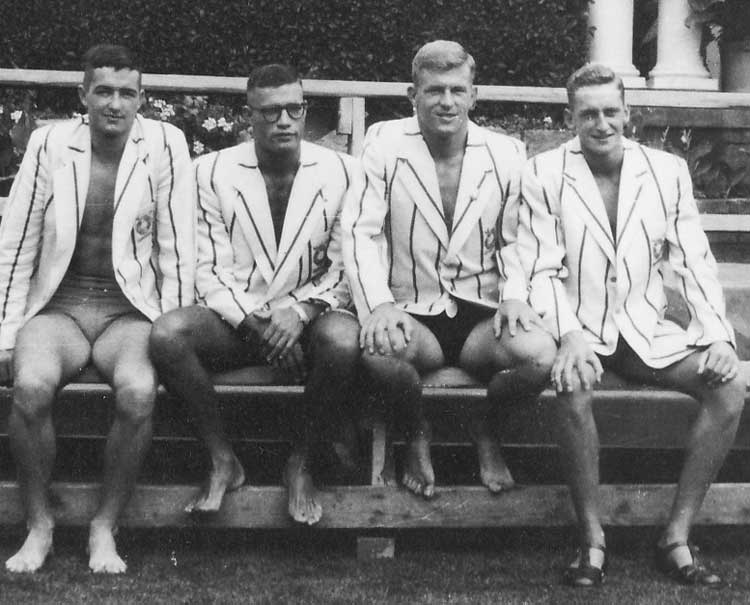

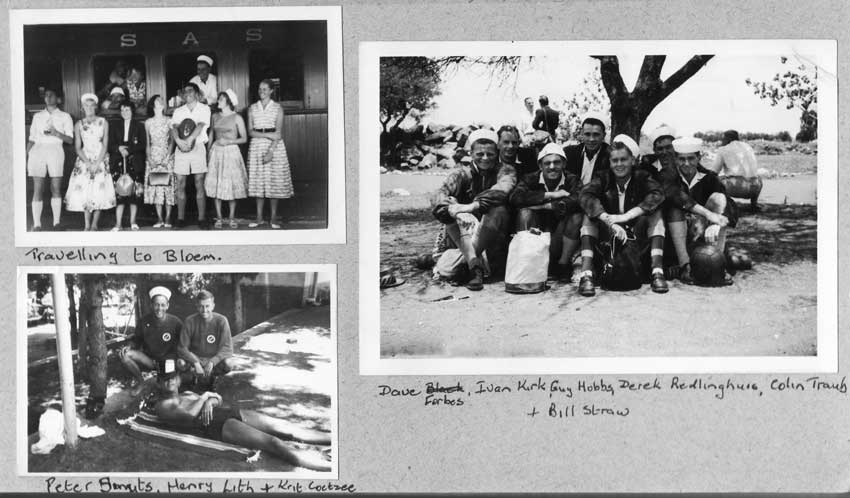

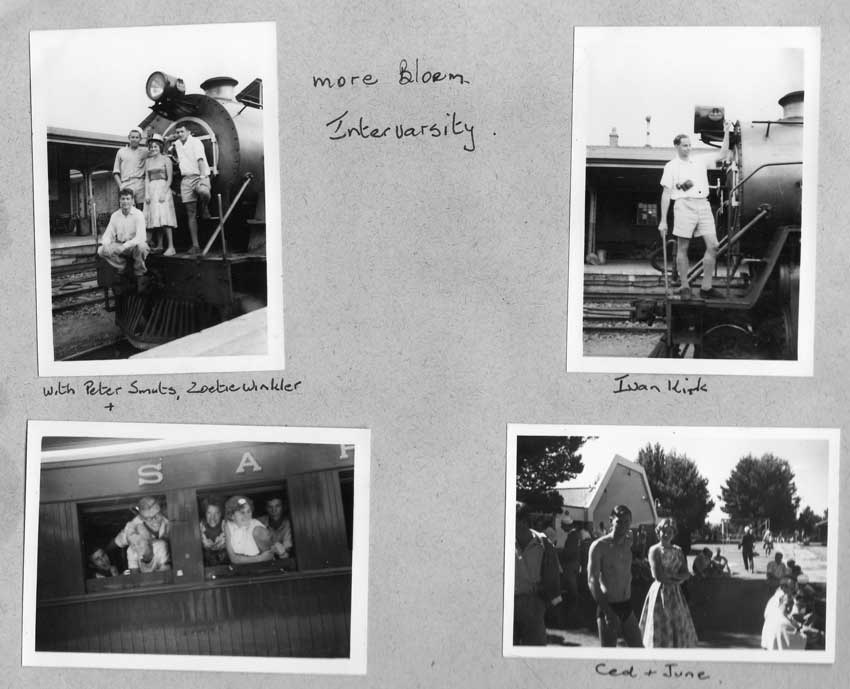

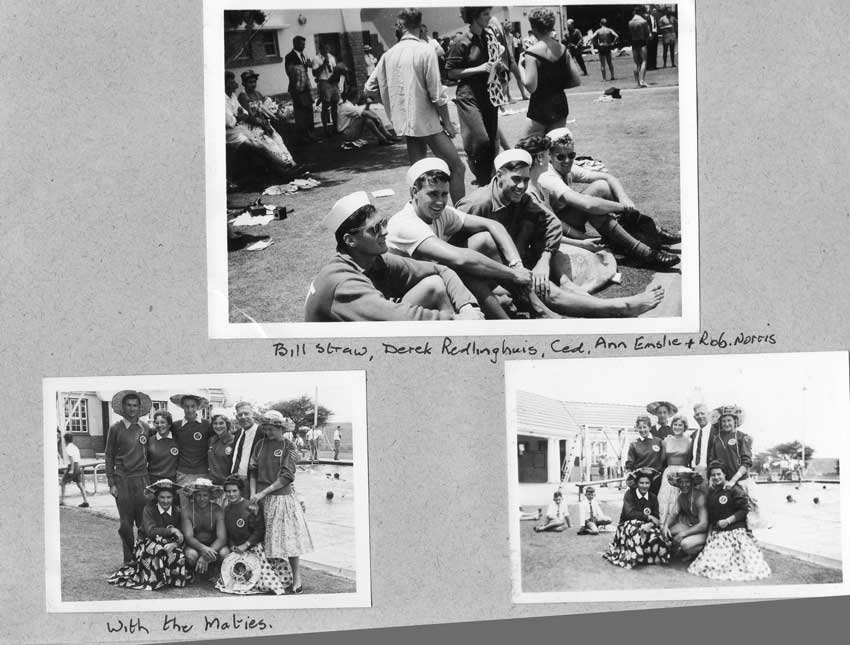

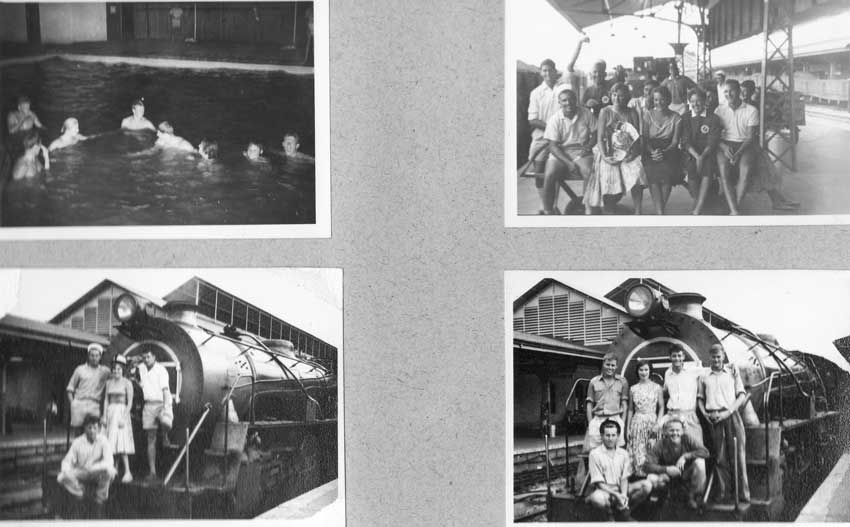

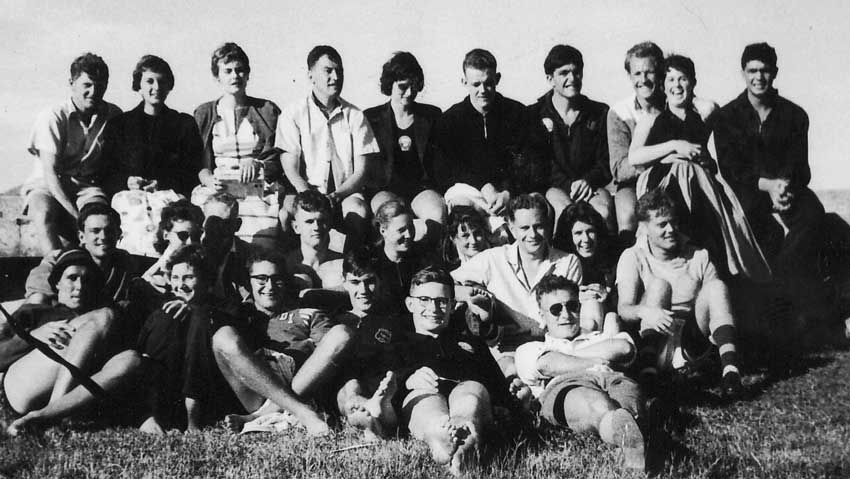

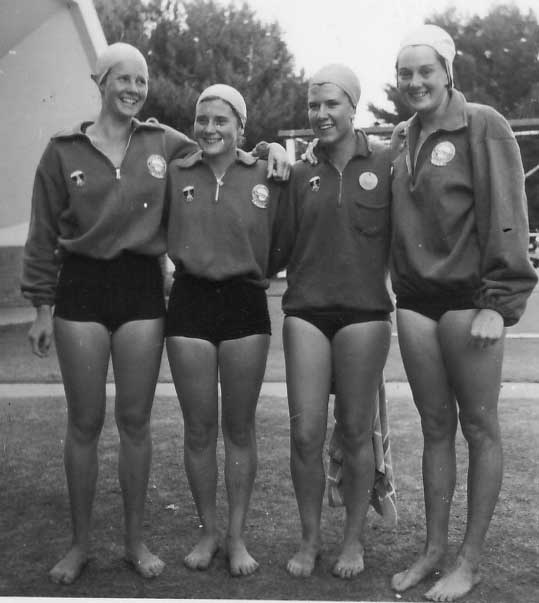

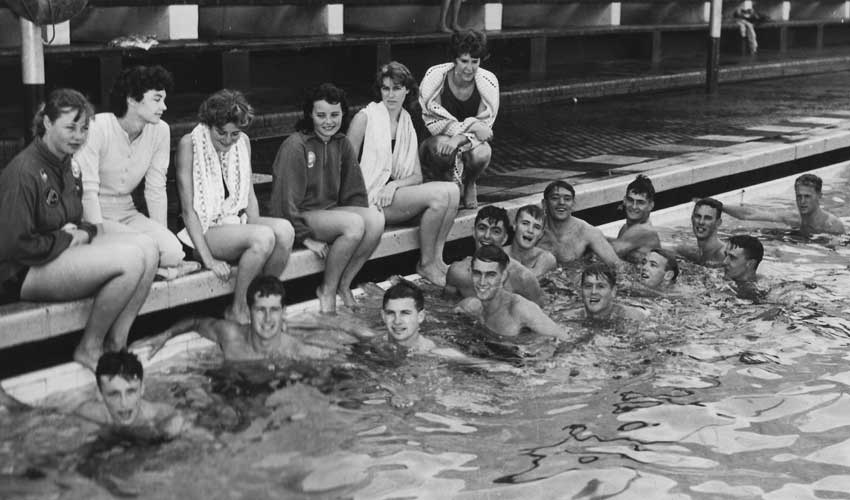

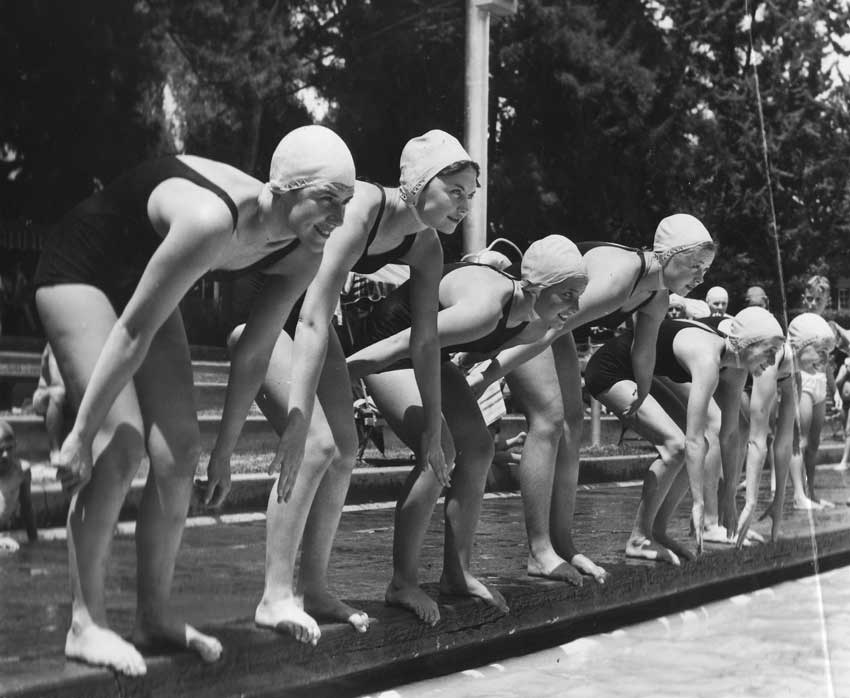

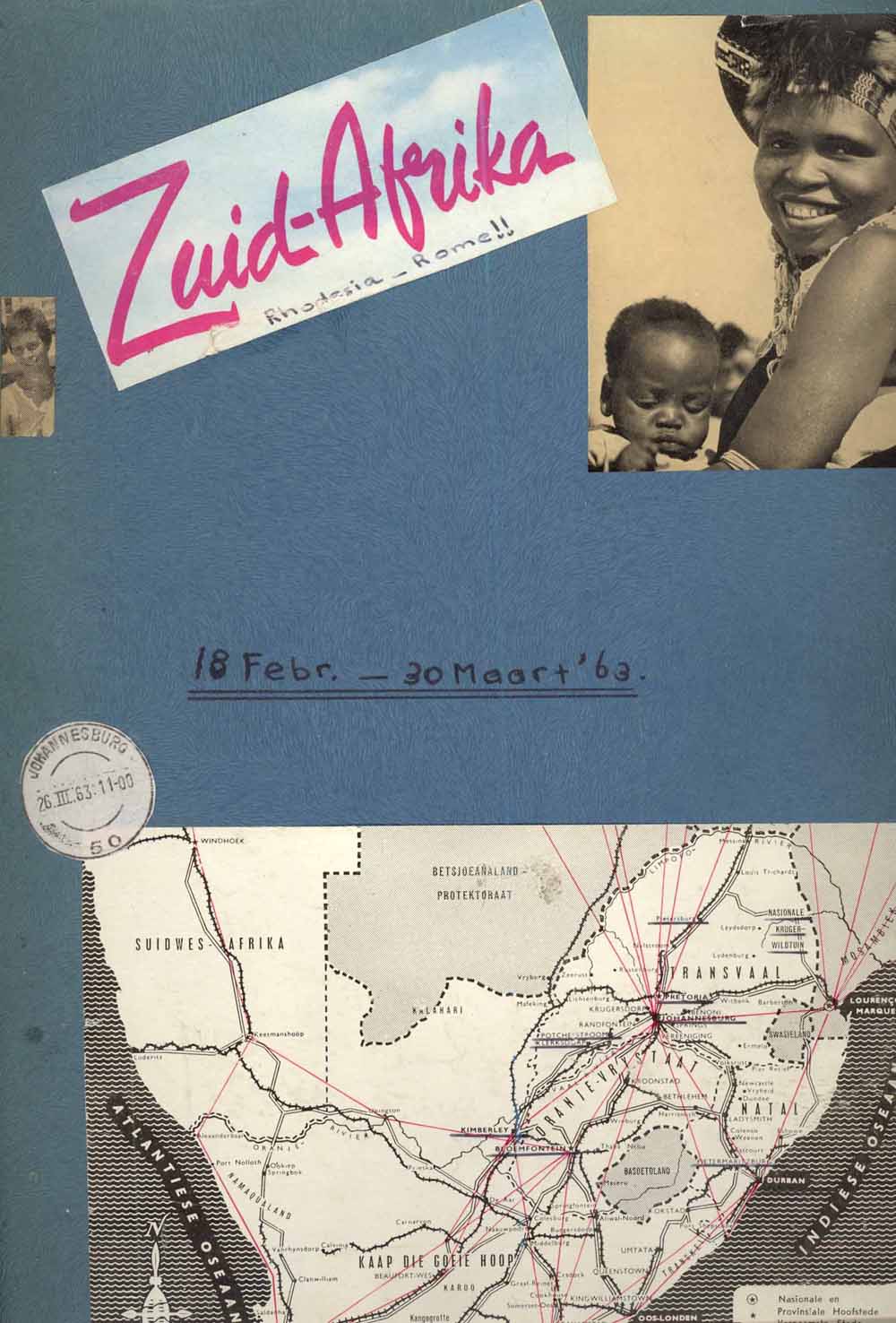

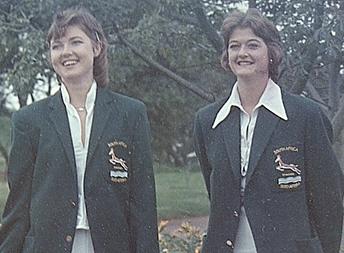

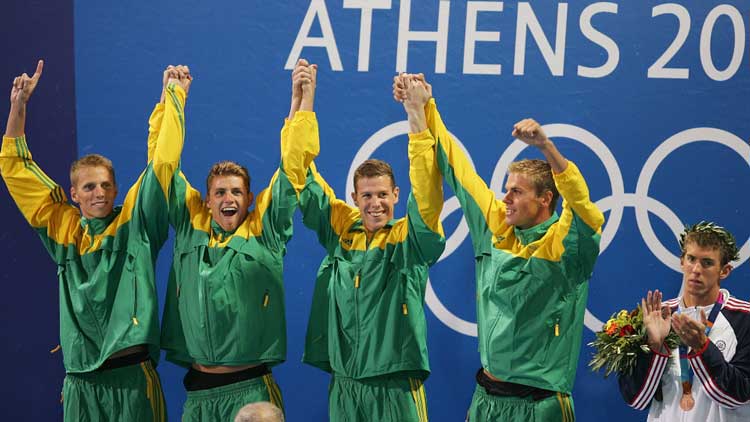

Champion disabled swimmers from southern Africa →

Today (2024), people with some disabilities compete in sports at the highest levels. There are 10 eligible impairment types in Para Athletics: eight physical impairments, vision impairment, and intellectual impairment. Deaf athletes compete at their own Deaflympics, or at the Olympic Games, like Terence Parkin did in 2000.

American gymnast George Eyser, who had a wooden leg, competed at the 1904 Summer Olympic Games and won three gold medals, and other disabled athletes competed at the Summer Olympic Games.

In May 2008, another amputee, Natalie du Toit of South Africa, qualified for the 2008 Beijing Olympics after finishing fourth in the 10 km open water race at the Open Water World Championships in Spain. She proved that disabled swimmers could compete at the highest levels of the sport.

Disabled sports in society

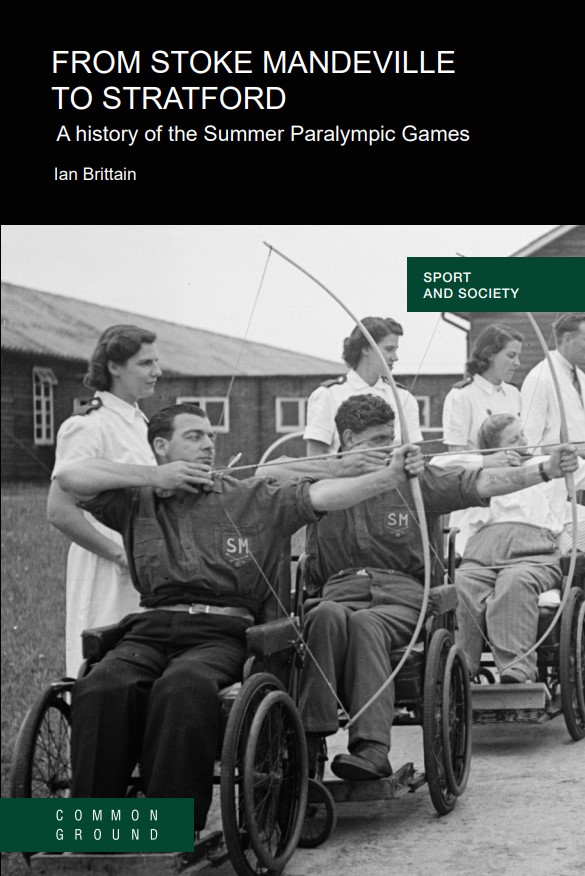

Paraplegic athletes (paralysed in lower limbs) started to participate in competitive sports in the late 1940s, with the establishment of the Stoke Mandeville Games, which later became the Paralympic Games and the World Abilitysport Games

Various organizations provide opportunities for disabled athletes to compete, such as the Paralympics, the Special Olympics, the World Ability Games, and the International Wheelchair and Amputee Sports Federation (IWAS). The definitions of disability and the debate surrounding appropriate definitions have evolved, leading to this proliferation of governing bodies that have different definitions and classifications of disabilities within which athletes compete against similarly disabled persons.

Disability sports, also known as adaptive or parasports, include a wide range of activities and competitive sports, such as Wheelchair rugby, Wheelchair tennis, Sitting volleyball, Inclusive dance, Accessible rambling, Boccia, Frame running, and Club throw.

The story of people with disabilities participating in sports is sad yet triumphant. Here is a short and incomplete history, as their stories are mostly unknown, and would best be told by themselves.

The term "disability" has grown from the earlier "cripple" and "paraplegic", which both refer to physical disabilities, to the concept of "parasport"

There are numerous definitions of disability and the debate surrounding appropriate definitions of disability have evolved over time. Disability sports, also known as adaptive or para sports, are sports for people with disabilities that are designed for or adapted to accommodate their needs

SOUTH AFRICAN SPORTS ASSOCIATION FOR PARAPLEGICS AND OTHER PHYSICALLY DISABLED

March 1979

Sport vir gestremdes staan onder beheer van die Suid Afrikaanse Sport Assosiasie vir Parapleëen en ander Liggaamlik gestremdes. Sport soorte ingesluit word genoem, die geskiedenis van sport vir gestrem des word kortliks geskets en die prestasies vein Suid-Afrikaanse sportlui op die gebied word bespreek. Kom petisie met normale sportlui vind nou ook plaas.

Sport for the disabled in South Africa is governed by the National Council of the South African Sports Association for Paraplegics and Other Physically Disabled.

Competitors from the Southern Transvaal, Western Transvaal, Northern Transvaal, Orange Free State, Griqualand West, Eastern Province, Natal, Western Province, South West Africa, Rhodesia, Transkei and Ciskei take part in the annual National Championships, where they compete in the following sports: archery, field events (discus, shot-put, javelin, precision javelin, club-throwing), swimming, weight-lifting, table tennis, basketball, snooker, bowls, wheelchair races (100m, 400m, 800m and 1 500m) and wheelchair slalom. In January 1977 the National Association of Blind Bowlers was accepted as an affiliated member.

In 1965 the Association registered its emblem with the Bureau of Heraldry. It depicts a springbok leaping through the wheel of a wheelchair and the badge is awarded to anyone selected to represent South Africa at an international meeting.

History of the International Paralympic Games →

Paraplegic athletes (paralysed in lower limbs) started to participate in competitive sports in the late 1940s, with the establishment of the Stoke Mandeville Games, which became the Paralympic Games and the World Abilitysport Games

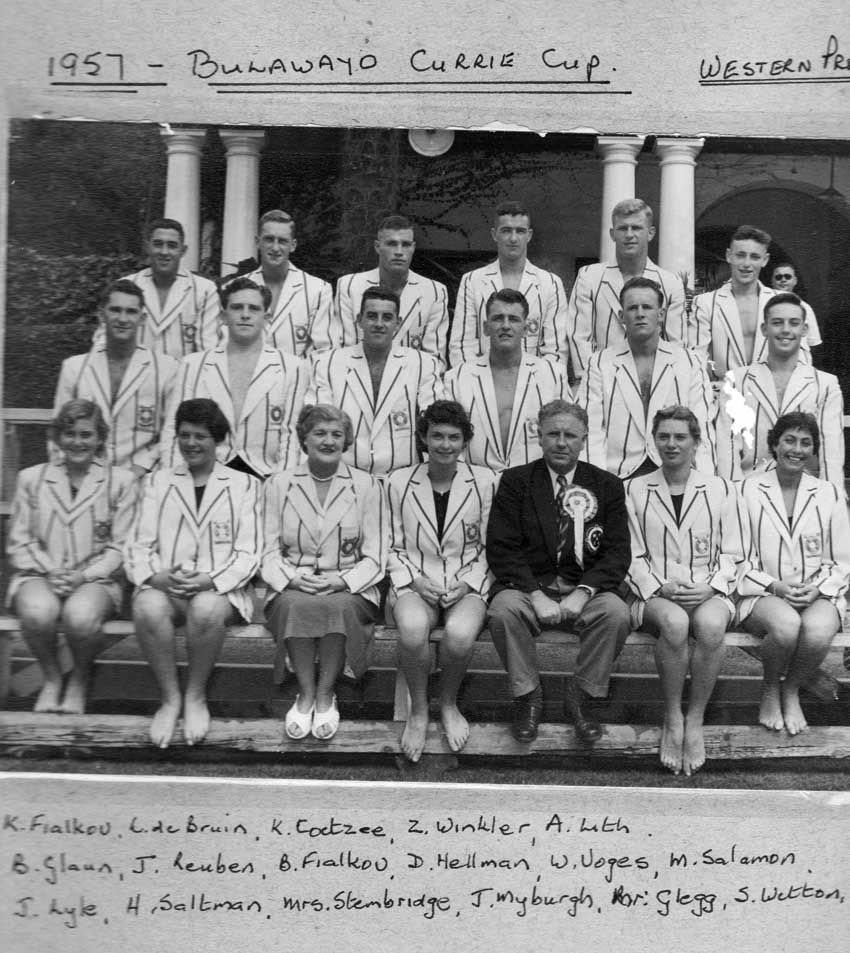

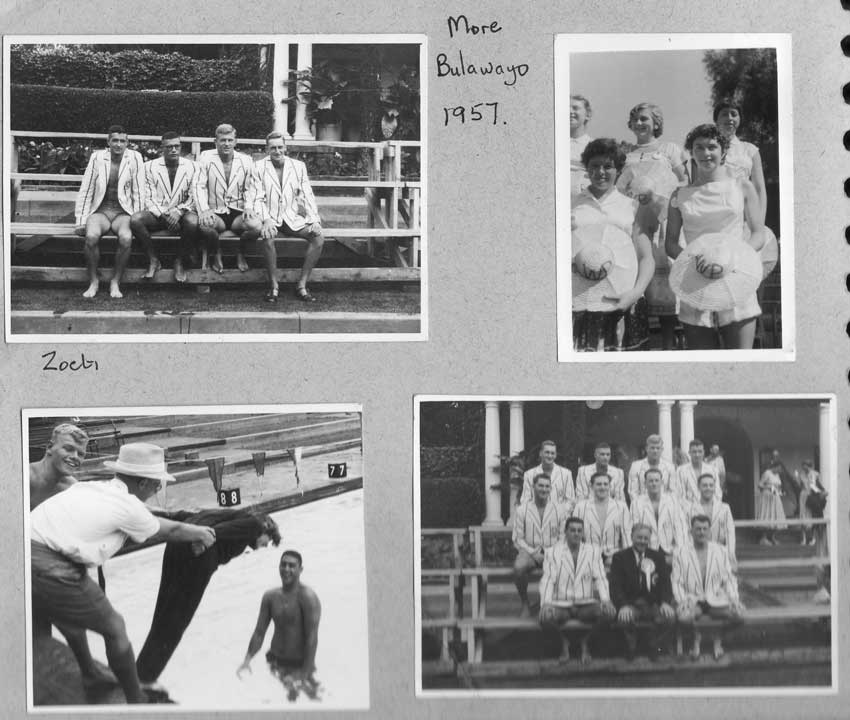

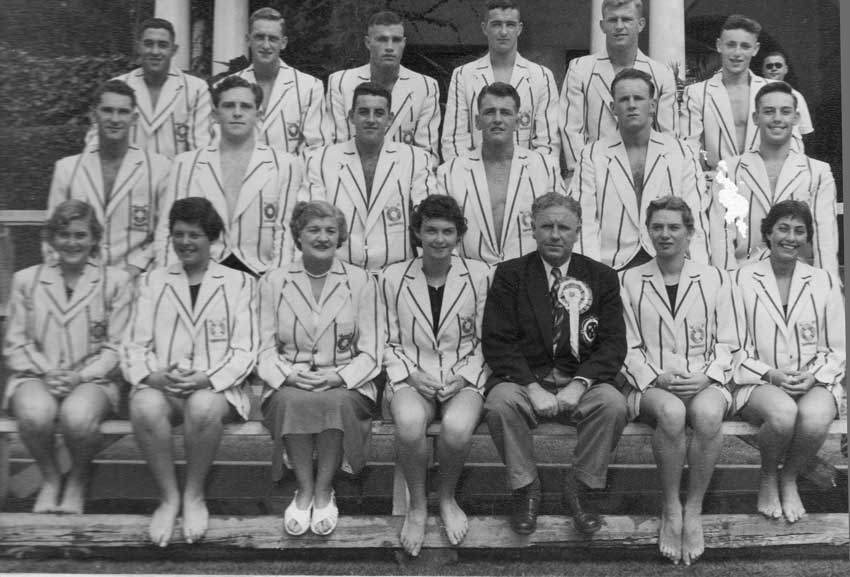

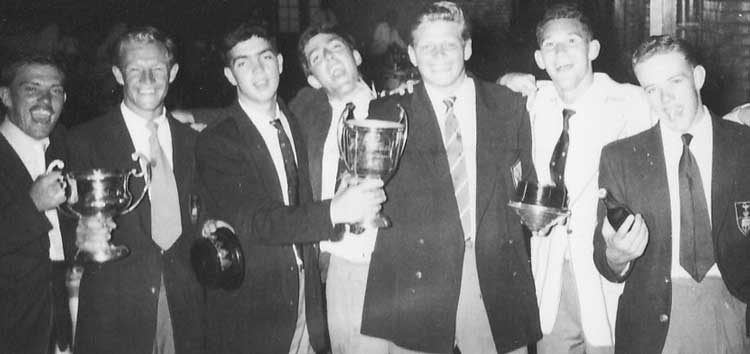

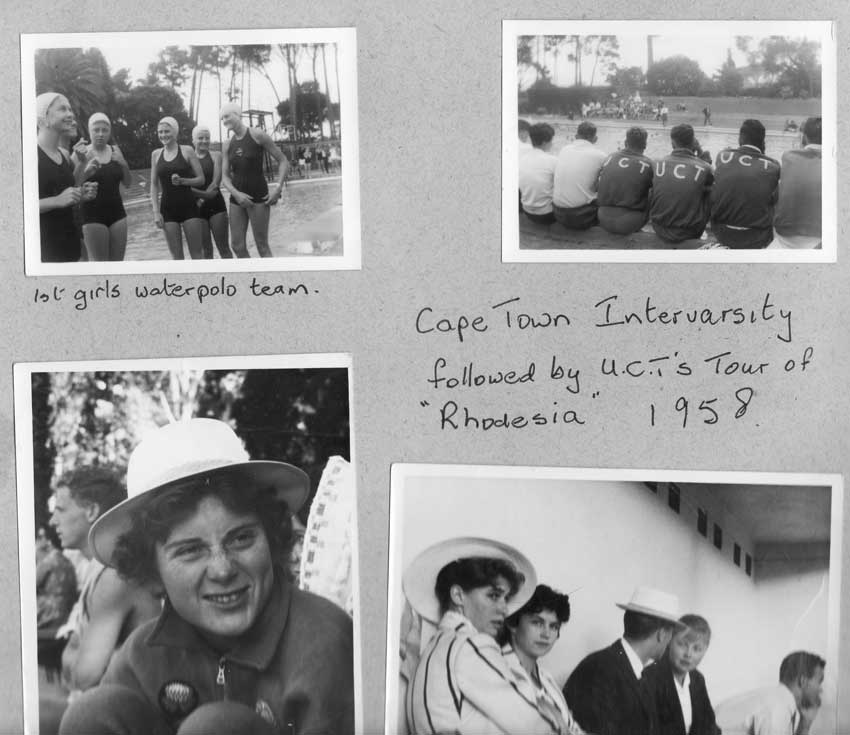

South Africans and Rhodesians have achieved considerable success in these events, particularly swimming. During the sports boycott era, Rhodesians continued to compete in South African events as a province, including paraplegic sports.

Both countries were allowed to continue participating in international paraplegic sporting events for much longer than their able-bodied countrymen. South Africa won 5 medals in swimming at the 1976 Paralympic Games in Toronto, although the Canadian government refused to grant visas for the Rhodesian Paralympic team to attend the 1976 Toronto Paralympics.

Sport for athletes with an impairment has existed for more than 100 years, and the first sports clubs for the deaf were already in existence in 1888 in Berlin.

It was not until after World War II, however, that it was widely introduced. The purpose of it at that time was to assist the large number of war veterans and civilians who had been injured during wartime.

In 1944, at the request of the British Government, Dr. Ludwig Guttmann opened a spinal injuries centre at the Stoke Mandeville Hospital in Great Britain, and in time, rehabilitation sport evolved to a recreational sport and then to competitive sports.

On 29 July 1948, the day of the Opening Ceremony of the London 1948 Olympic Games, Guttmann organised the first competition for wheelchair athletes which he named the Stoke Mandeville Games which was a milestone in Paralympic history. They involved 16 injured servicemen and women who took part in archery.

Paraplegic sport (which the Paralympics is named after) grew after that 1948 event. Beginning in 1960 during Summer Olympic years, the International Stoke Mandeville Games (ISMG) were held in the same host city as the Summer Olympics. These particular editions of the Games were retroactively recognised as being the first four Paralympic Games. The Games were otherwise hosted in Stoke Mandeville in all other years. Beginning in 1976, the Paralympic Games began hosting events for amputees and the visually impaired; at this point, the Paralympics were no longer credited as being editions of the ISMG, but the ISMG went on hiatus during Paralympic years.

After the Paralympics expanded to include events for disability classifications other than wheelchairs, the ISMG for wheelchair athletes continued to be hosted annually in Stoke Mandeville, and later other countries, in all non-Paralympic years.

1949 saw the second of the Stoke Mandeville Games, in which 37 individuals participated. In addition to a repeat of the previous year’s archery competition ‘net-ball’ was added to the programme for these Games. This was a kind of hybrid of netball and basketball played in wheelchairs and using netball posts for goals. Only one team fielded a woman in their team, 21-year-old Margaret Harriman (neé Webb), who at age 19, she sustained a fractured spine in a tractor accident. She emigrated to Rhodesia and later to South Africa, becoming one of the most successful Paralympians between 1960 and 1996.

An unnamed patient from Southern Rhodesia participated in the 1951 event, and a similarly anonymous South African competed in 1953 when swimming was also added to the list of sports at the Games.

In 1962 the South African Paraplegic Games Association was established. It was only for persons with spinal cord injuries.

South Africa first competed in the International Stoke Mandeville Games, which in an Olympic year became known as the Paralympic Games, in 1962.

The Paralympics concept was introduced in South Africa in 1963 and was included in the first South African National Games held in Johannesburg in March 1964.

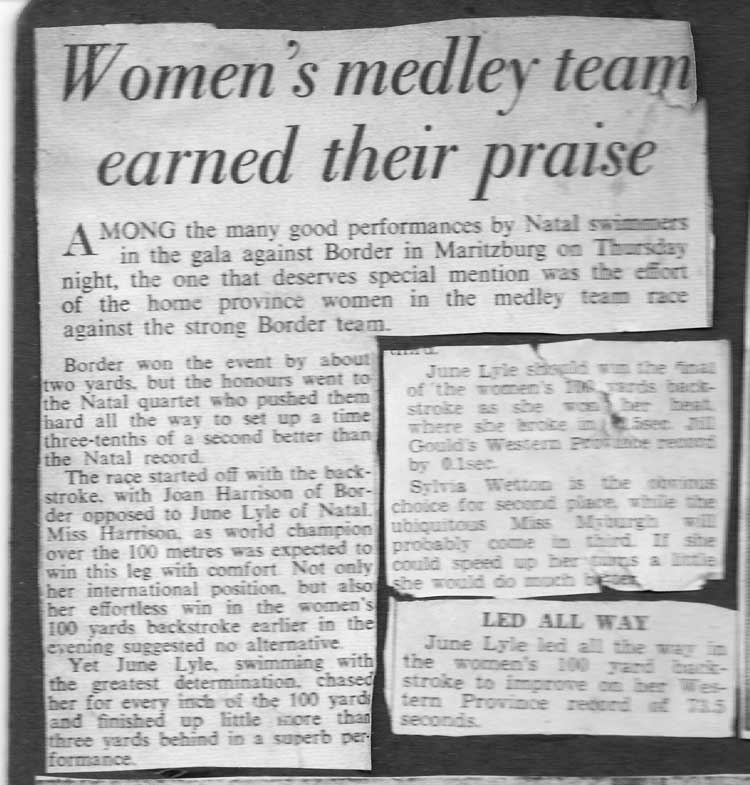

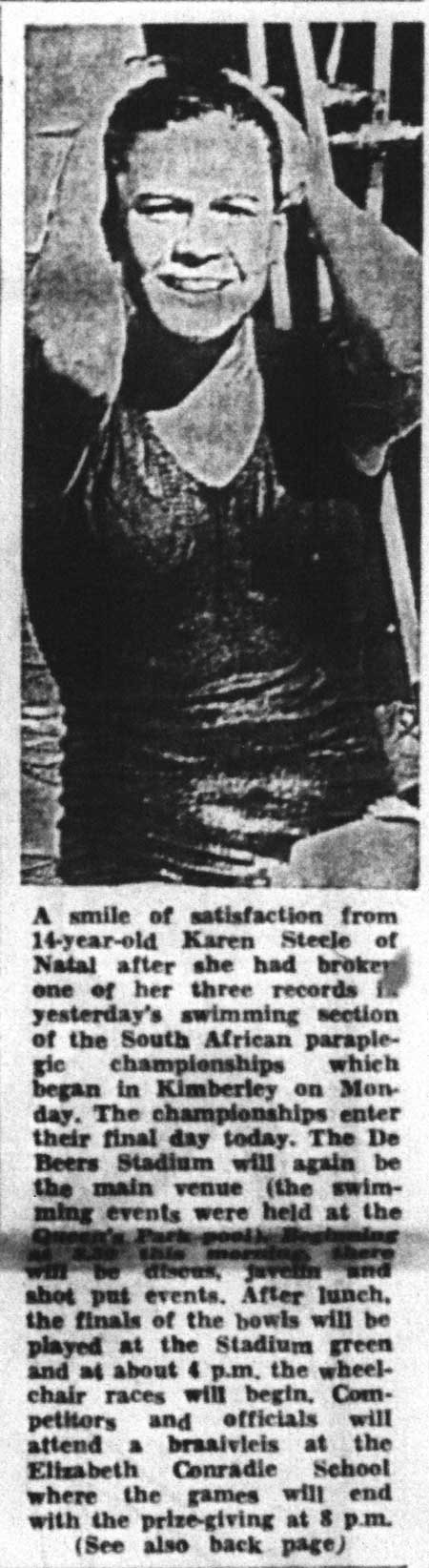

1968 - Karen Steele of Natal paraplegic swimmer at the South African Championships in Kimberley.

SOUTH AFRICAN SPORTS ASSOCIATION FOR PARAPLEGICS AND OTHER PHYSICALLY DISABLED

March 1979

Sport vir gestremdes staan onder beheer van die Suid Afrikaanse Sport Assosiasie vir Parapleëen en ander Liggaamlik gestremdes. Sport soorte ingesluit word genoem, die geskiedenis van sport vir gestrem des word kortliks geskets en die prestasies vein Suid-Afrikaanse sportlui op die gebied word bespreek. Kom petisie met normale sportlui vind nou ook plaas.

Sport for the disabled in South Africa is governed by the National Council of the South African Sports Association for Paraplegics and Other Physically Disabled.

Competitors from the Southern Transvaal, Western Transvaal, Northern Transvaal, Orange Free State, Griqualand West, Eastern Province, Natal, Western Province, South West Africa, Rhodesia, Transkei and Ciskei take part in the annual National Championships, where they compete in the following sports: archery, field events (discus, shot-put, javelin, precision javelin, club-throwing), swimming, weight-lifting, table tennis, basketball, snooker, bowls, wheelchair races (100m, 400m, 800m and 1 500m) and wheelchair slalom. In January 1977 the National Association of Blind Bowlers was accepted as an affiliated member.

In 1965 the Association registered its emblem with the Bureau of Heraldry. It depicts a springbok leaping through the wheel of a wheelchair and the badge is awarded to anyone selected to represent South Africa at an international meeting.

ELIZABETH CONRADIE SCHOOL

In a unique co-operation between the National Departments of Defence, Health and Labour, boys with rehabilitative disabilities who reported for military service, were grouped during 1939 in special peletons at Voortrekkerhoogte in Pretoria.

Early 1941 these peletons grew into a battallion and from 1942 the Physical Training Battallion was launched under Major Danie Craven. Since September 1942 the Physical Training Battallion also became a school at Voortrekkerhoogte and by 1945 it was a very good school with 660 disabled boys and 32 teachers. After the Second World War, the school moved early in 1946 to the old Army Base in Kimberley.

The post office at the base was called Diskobolos, and so the school was also informally called Diskobolos. The then Union Education Department took over control of the Physical Training Brigade School. The symbol of the school was the statue of the discus thrower – the Diskobolos statue.

The 166 staff members of the school comprised of medical doctors, psychologists, vice principals, teachers, therapists, a statistician, a photographer, a sociologist, dieticians, a butcher, an investigator (policeman), a farm foreman and a sports organizer. Dr Danie Craven was the director (principal) of the school. In April 1950 the school ceased to exist as the Physical Training Brigade focussed on rehabilitative disabilities. Since 1948 pressure was put on the school to also enroll learners with non-rehabilitative disabilities.

So learners on crutches and in wheelchairs were also enrolled, and three different schools came into being: a boys school for boys with physical disabilities, a girls school for girls with physical disabilities, a high school ("beroepskool") for boys with physical disabilities.

In April 1955 the Girls School moved from picturesque and historical Alexandersfontein (where Cecil John Rhodes and his friends played) to Diskobolos. One school was formed, Elizabeth Conradie School. The school was named after the wife of the then Administrator of the Cape Province, Dr Johanna Elizabeth Conradie as she was the dynamic president of the National Cripple Care Council. When PW Botha, Minister of Defence, indicated that the military needed the Diskobolos facilities, a new school was planned and built in Kimberley.

On 1 December 1973 Elizabeth Conradie School moved to the current premises next to the N12 road.

https://elconwebsite.wixsite.com/elconwebsite/history

Warm feelings after Flamingo Aquatics’ icy plunge at Elcon

By Danie van der Lith - Sep 13, 2024

Flamingo Aquatics recently hosted their much-anticipated annual fund-raiser, featuring a polar plunge at Kimberley’s Elizabeth Conradie School aimed at uniting the community, promoting swimming, and supporting local schools.

ADMIT it, there’s nothing you’d enjoy more on these chilly Spring mornings than to plunge into the icy water of a swimming pool still chilled from our freezing winter …

No? Me neither! But that’s precisely what a group of swimming enthusiasts did recently.

Flamingo Aquatics recently hosted their much-anticipated annual fund-raiser, featuring a polar plunge at Kimberley’s Elizabeth Conradie School. The event was designed to unite the community, promote swimming, and support local schools simultaneously.

But in a heartwarming and exciting development, Flamingo Aquatics announced a partnership with Elizabeth Conradie School to promote swimming at the institution.

Plans are also under way to introduce the “Learn to Swim” programme on the school’s premises. This initiative will offer swimming lessons not only to the school’s learners but also to members of the public, providing an invaluable opportunity for both students and the wider community to learn essential swimming skills.

Speaking to the deputy principal of Elizabeth Conradie School, Johan van Zyl, it was clear that the day was a success. “Saturday was a true ‘dream come true’ for me and Mrs. van Zyl. It has always been her vision to restore the outdoor swimming pool to its full glory. Mrs. van Zyl and I share this vision and have been looking for the perfect opportunity to officially inaugurate the pool,” he said.

Van Zyl said that the Flamingos’ Polar Plunge was the ideal opportunity. It was the first official event held at the pool since the renovations.

“It meant a lot to our learners, as they could socialise on a different level and enter the water with full confidence. With the ‘fun and games’ and the treats from Flamingos, our learners could socialise with Christina Kiddies and other swimmers. THANK YOU AGAIN!

Van Zyl, who is also part of Flamingo Aquatics, said that swimming embodies an important therapeutic aspect that is crucial for learners with physical disabilities. “As a school, we look forward to partnering with Flamingo Aquatics again to breathe life into swimming at the school. Flamingos are more than welcome to network with the school again regarding swimming and the promotion of swimming in schools.”

As part of the event, Christina Kiddie Child Centre was invited to share in the festivities, giving the children a special day to remember. The young ones braved the icy waters of the pool for a polar plunge, followed by lively games such as tug of war and egg races.

The cold temperatures didn’t cool their enthusiasm, as the day was filled with laughter, smiles, and a sense of unity.

“The joy on the children’s faces was undeniable,” a representative from Flamingo Aquatics told the DFA. “It was a heartwarming sight to see them enjoying themselves despite the chill.”

The event highlighted the power of togetherness and the importance of creating opportunities for fun and recreation within the community. It was a day that will surely be remembered fondly by all who attended, as Flamingo Aquatics continues its mission to promote swimming and water safety in Kimberley.

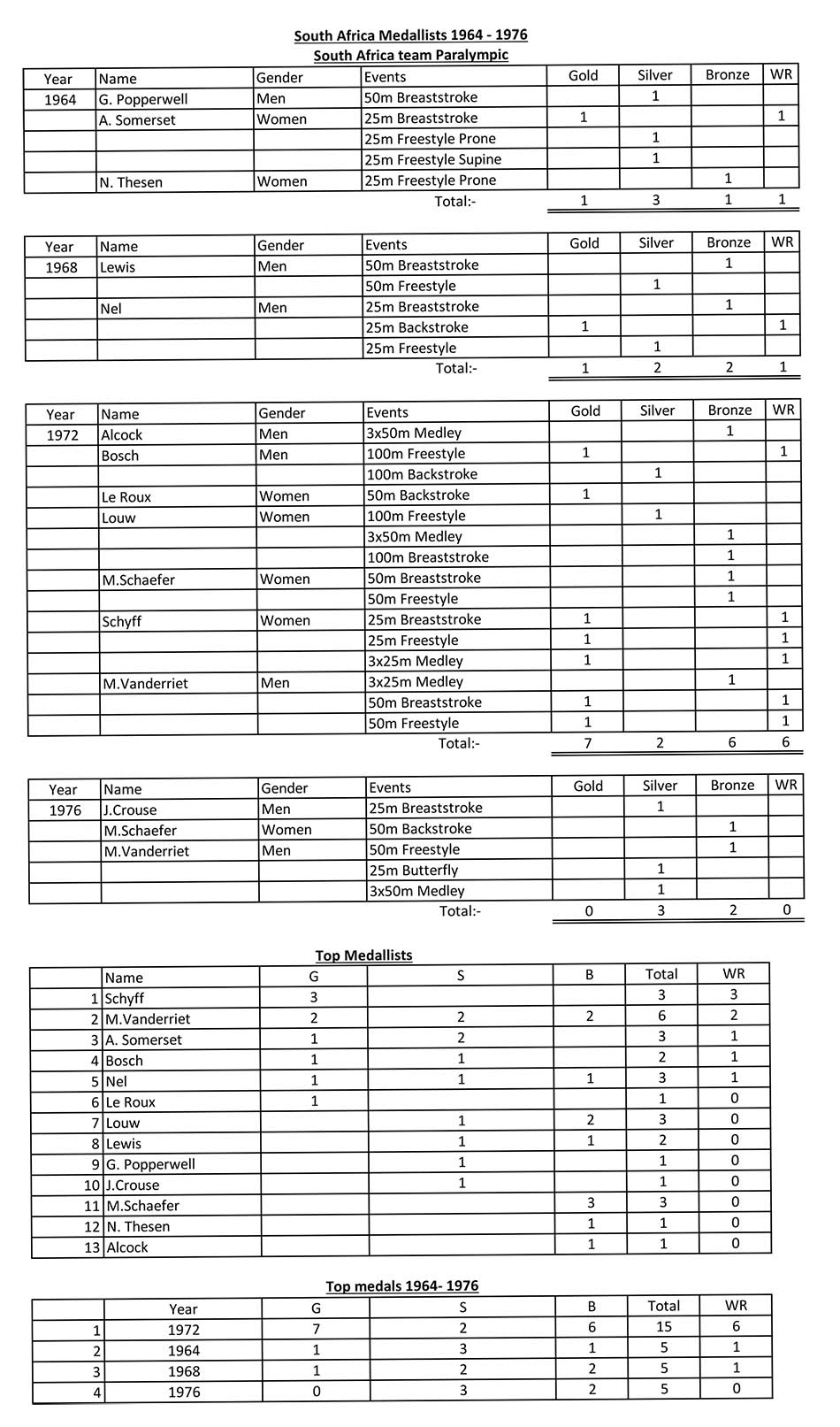

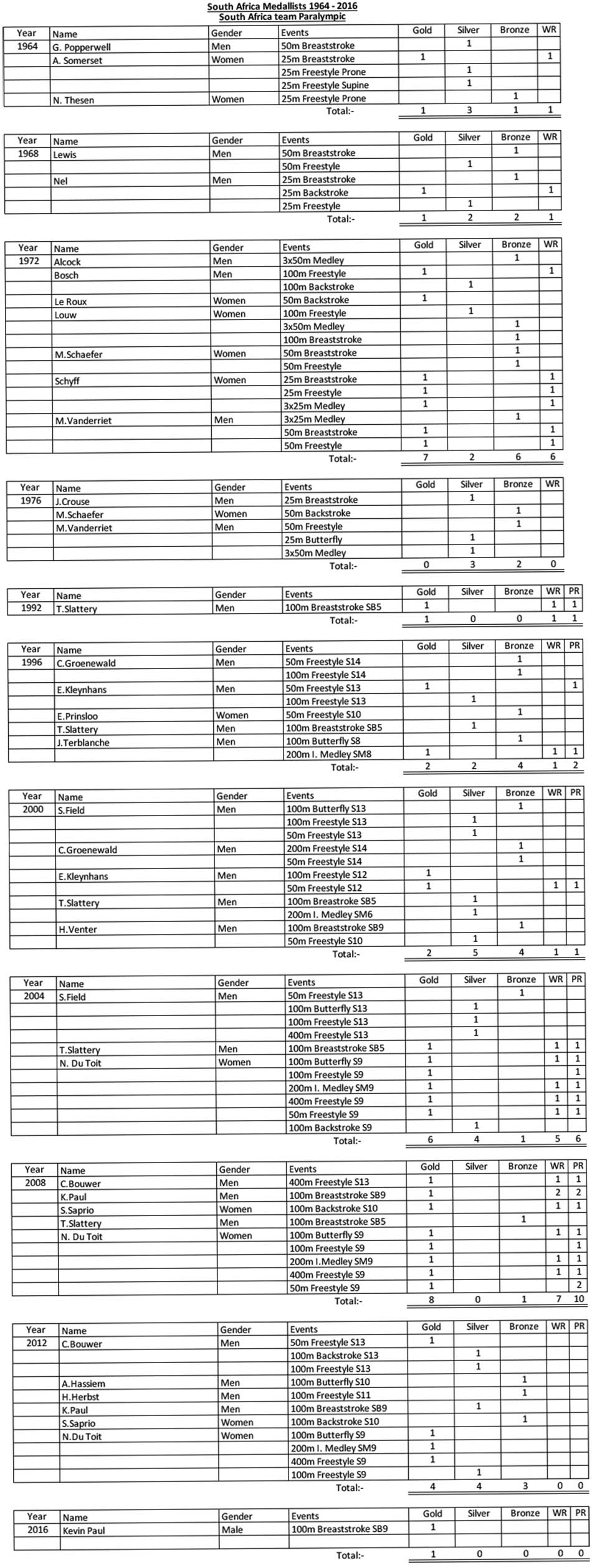

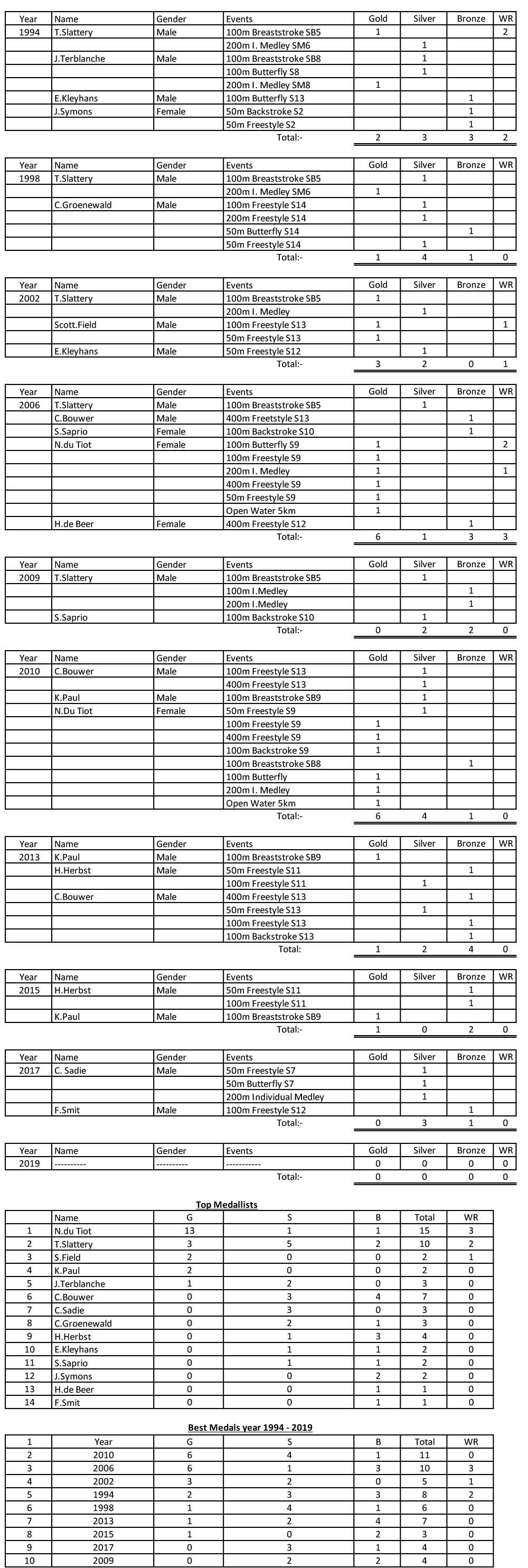

South African Medallists Paralympics 1964 - 1976

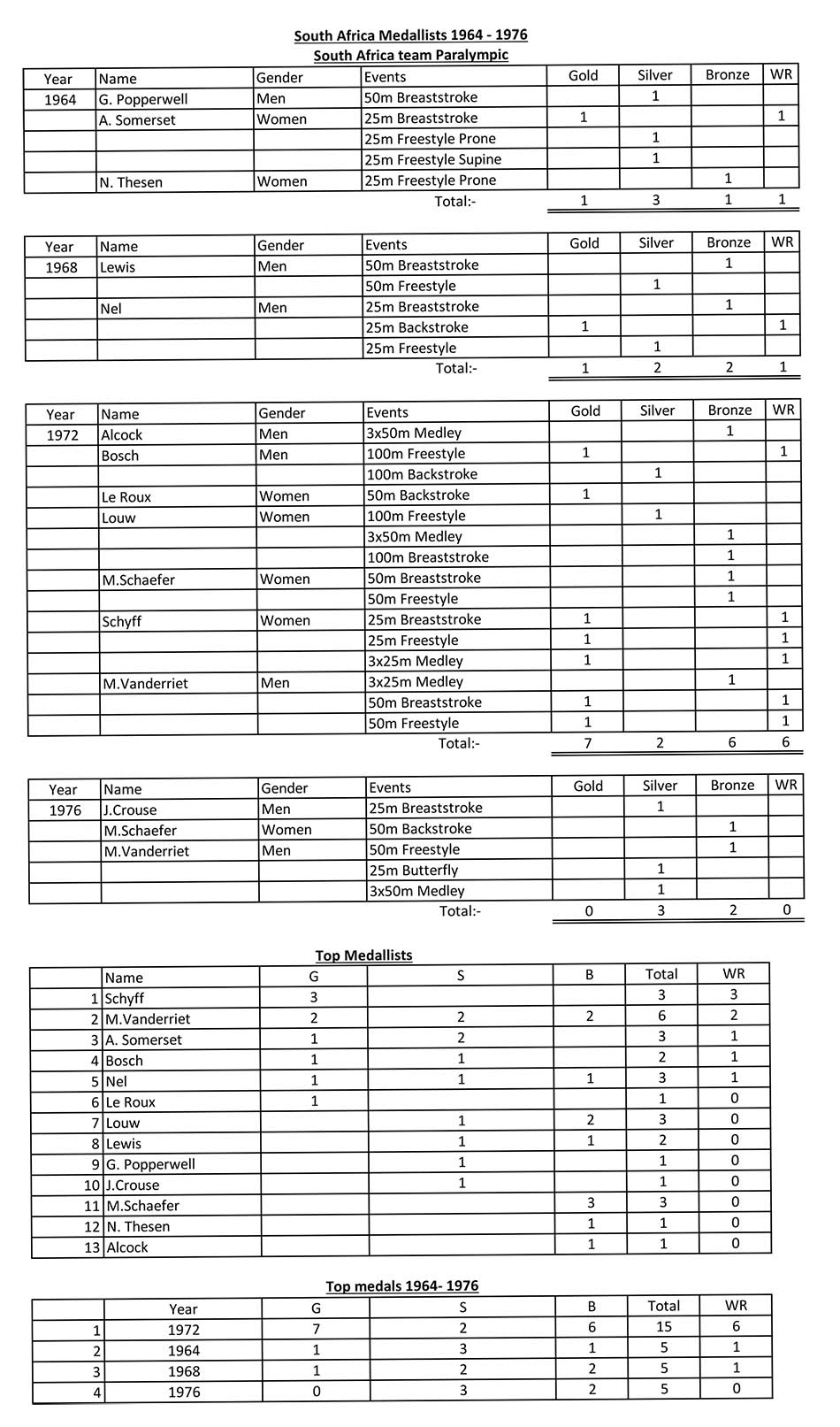

World Championships medals 1994-2019

Women

| Rank | Athlete | Games | Gold | Silver | Bronze | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | DU TOIT Natalie | 2004-2012 | 13 | 2 | 0 | 15 |

| 2 | SCHYFF | 1972 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| 3 | SOMERSET A. | 1964 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 3 |

| 4 | SAPIRO Shireen | 2008-2012 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| 5 | LOUW | 1972 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 6 | SCHAEFER M. | 1972-1976 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 |

Men

| Rank | Athlete | Games | Gold | Silver | Bronze | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | KLEYNHANS Ebert | 1996-2000 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 4 |

| 2 | SLATTERY Tadhg | 1992-2008 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 6 |

| 3 | VANDERRIET M. | 1972-1976 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 6 |

| 4 | BOUWER Charles | 2008-2012 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 4 |

| 5 | PAUL Kevin | 2008-2016 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| 6 | NEL | 1968 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| 7 | BOSCH | 1972 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| 8 | TERBLANCHE J. | 1996 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| 9 | FIELD Scott | 2000-2004 | 0 | 5 | 2 | 7 |

| 10 | LEWIS | 1968 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| VENTER Hannes | 2000 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |

| 12 | GROENEWALD Craig | 1996-2000 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 4 |

- Hits: 6053