Louis Grundlingh Professor in the department of Historical Studies at the University of Johannesburg

Introduction

After the discovery of gold in 1886, a mining camp was established with no intent of any later development into a town, let alone a city. However, mass migration to the lucrative gold fields soon took off. It became clear that Johannesburg would indeed become a permanent settlement.

This population increase prompted the government of the Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek (South African Republic) to provide proper town planning. The town surveyor decided on a grid system of small blocks and small stands. The reasoning was to earn as much revenue as possible for the government because rent had to be paid for the stands. This layout limited any provision for urban open spaces. As a result the only significant open spaces that featured in the 1887 plan was the market square.

Until 1902, Johannesburg did not have a town council (hereafter, council). However, at the end of the South African War in 1902, the situation changed. The British government under the leadership of Lord Alfred Milner, took over the administration of Johannesburg from military control and set up an effective municipality, based mainly on the British model. As part of its post-war reconstruction agenda the town council seamlessly integrated British ideas into their vision of Johannesburg's further development. Consequently, it embarked on the provision of proper public services to the fledgling town, such as infrastructure, town planning and the provision of water, electricity and transport. This was in line with the requirements of an early 2Oth-century "garden city", where these services were seen as essential.

Very little academic research has been done thus far on Johannesburg's open spaces and particularly their development into major sport venues. This paper aims to rectify this by investigating the history of Ellis Park. Ellis Park is exceptional in four ways. It never really had the characteristics of a traditional "park". It is one of the first areas in Johannesburg developed on the grounds of an early reservoir which fell into disuse. The initial aim was to develop the grounds into a lake for recreational boating. Lastly, from 1905 to the 1930s the grounds were transformed into one of South Africa's most famous fully-fledged sport arenas.

This article argues that it was especially health consciousness amongst Johannesburg's white residents, as well as the prestige of having an open space for first class sport facilities within the context of the "modern city" movement, that prompted this development. The essay further investigates the considerations leading to the council's decision to make this huge investment, as well as the major role of the Transvaal Rugby Football Union (TRFU) in the later development of Ellis Park. Lastly, the essay describes the physical changes to provide for a wide range of sporting activities such as athletics, tennis, rugby football and swimming. This essay does not purport to follow a "history from below" approach but rather it investigates the roles of the political powerful, i.e. Johannesburg's town council and the sport administrators.

Four factors made it possible to develop Johannesburg into a "modern" city. Because of the huge profits from the gold mines a wealthy urban white elite, the so-called Randlords, or mining magnates, settled and invested in the city. Secondly, there was a strong political will. Thirdly, by the 1900s, population increase amongst whites in the inner-city, noise and pollution led to the outward expansion into the suburbs. Fourthly, as mentioned, the council was ideologically aligned with its counterparts in Britain and subscribed to the British mindset on the necessity of open urban spaces. This meant that the council ear-marked a number of open spaces for development into public parks for play, relaxation and organised sport. The history of urban open spaces and their value, reflects these diverse functions. In Johannesburg, Ellis Park was a case in point.

**Dust from the mine dumps often made outdoor activities unpleasant. Ironically, though, with moderate weather eight months of the year, Johannesburg's climatic conditions favoured outdoor sport activity. Even though some summer days could be warm to hot, often a late afternoon thunderstorm provided welcome relief.9 Supported by excellent weather, Johannesburg's rapid population growth, and the growing awareness of the advantages of a healthy lifestyle, set the scene for outdoor activities such as tennis, boating, cycling and swimming. The initial incentive was indeed the need for a municipal swimming pool which had been considered from time to time by the council from as early as 1904.

The next step was to locate a site for the establishment of Ellis Park. Initially, considerations such as the lack of a cheap water supply, capital funds for a swimming pool as well as high prices for land, kept the start of the project in abeyance. There was, however, land on which two disused open reservoirs and the Doornfontein brickfields were situated - a "sort of no-man's land" of shacks and hovels occupied by Coloured washerwomen and black people. This land, between North Park Lane and Eryn Street to the north/north-west; Bertrams Road to the east and South Park Lane and Reservoir Street to the south in New Doornfontein, belonged to the Rand Water Board and the Johannesburg Waterworks Estate and Exploration Company.

A major asset of the grounds was the borehole, at the time the main source of water for the neighbourhood. The reservoir site comprised 25 acres (10 ha) and had become derelict by the turn of the 19thcentury. In 1908 the council bought the Rand Water Board's lease for £2 500 and paid £500 to the Johannesburg Estates Company for a further 7 acres (2,8 ha) adjoining the reservoir site. With J.D. Ellis as the driving force, and instrumental in conceiving and converting the neglected site into a playing ground, the council embarked on a comprehensive reclamation scheme with a "grand vision" of an all-encompassing sports centre for Johannesburg.

One of the first developments towards developing the park into a sports ground was the adaptation of the old storage dam into an artificial lake to be used for boating. Tenders were invited for the right to hire out small boats. The tender was awarded to S.M. Hershfield for 12 months at £20 a month. Hershfield did not have the sole right of boats on the lake because permission was also granted to private persons to have boats, provided they did not compete with his business. When the contract expired the next year, the only tender was that of J. Goodman at £10 per month which the council approved.

Despite the financial losses, it seems the lake would remain a permanent feature in the development of Ellis Park. In August 1910 the town council approved expenditure for the building of a pathway around the lake because the nature of the embankment around the lake was considered dangerous as children might fall into the water. The expenditure would be £974, which was a substantial amount at the time. Even as late as March 1912, the council confirmed its contract with Messrs Bagguley and Stephens "for the completion of the Lake in Ellis Park and the excavation and removal of soil from the Park". Nevertheless, it seems that nothing came of this plan. The council still maintained its vision to provide for recreation by developing the grounds into rugby football fields, tennis courts, cricket grounds and a swimming pool. At the end of 1908, a report in the Rand Daily Mail noted: "Ellis Park", the thirty acres of town pleasure ground so attractively nestling between the thickly populated sides of the Doornfontein and Fairview Hills, is gradually evolving from the unsightliness of the donga stage."

Swimming bath

The first step towards the "grand vision" was the construction of a swimming bath that would become a central feature. The decision to build the bath was not taken on a whim. By then the council had already received inquiries from numerous sports clubs to lease portions of ground in Ellis Park for tennis and racquet courts, croquet lawns, football grounds, an ice skating rink and an entertainment hall.

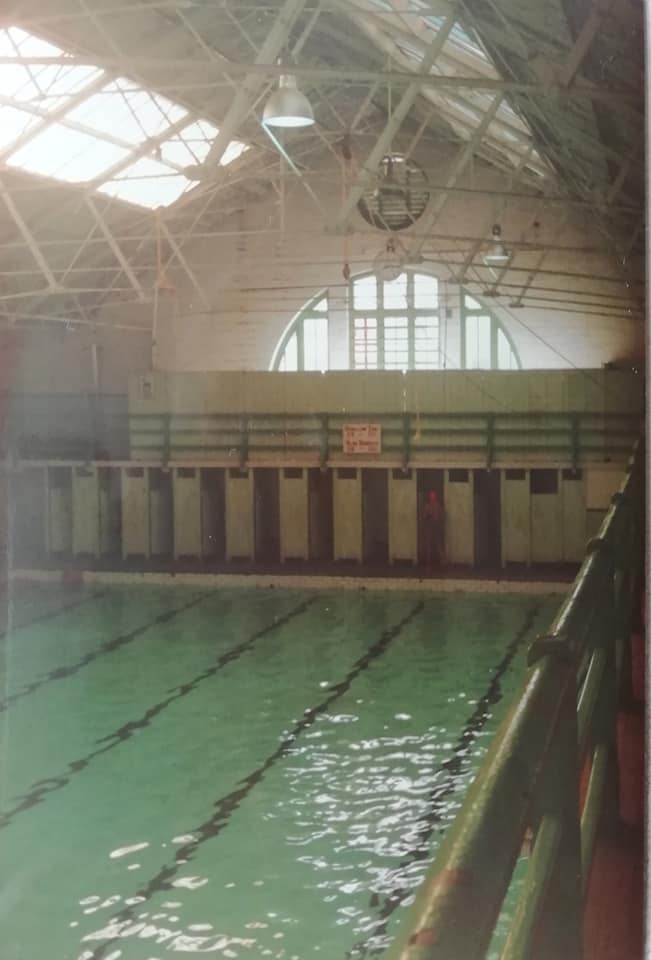

A Mr Dowsett, of the municipality's architectural branch and a water "fanatic" was tasked to oversee the building. A bath of 150 feet (45.72 metres) long, 100 feet (30.5 metres) wide and 3 feet 4 in (1 metre) to 7 feet 4 in (2.2 metres) deep was proposed. In July 1908 the council decided to award the tender to Messrs Harper Brothers to build the bath28 - at that time the largest in South Africa. In line with the notion to develop Ellis Park into a first class sport venue, the design provided for international competitions. In addition, accommodation for 3 000 people, dressing rooms, a children's shelter and ticket office were built. The Rand Daily Mail journalist could write: "The glittering tiles have almost obscured for ever the bottom of what was once Johannesburg's first reservoir for the town's drink."

On Saturday 16 January 1909, the first public swimming bath in Johannesburg was inaugurated with a grand gala. The Sunday Times reported:

The best three hours of aquatic sport [that] Johannesburg has yet experienced were enjoyed by over 2 000 people … For the first time the general public had an opportunity of seeing what has been done for them … The trees and seats which run around two sides of the water were crowded with visitors of both sexes, the threat of rain being insufficient to keep them away from the prospect of sport … The bath itself is certainly the most adequate structure of its kind in the subcontinent for races … it seems pretty certain that there will be no lack of public support for fixtures as that of yesterday.

Within three years this prediction proved to be spot-on. The popularity of the bath was evident: "There are glad tidings for a long-suffering public. The swimming baths in Ellis Park are to be opened again for the summer season on Saturday, and preparations are being made for dealing with a rush." Cheap tickets, open hours from 6 am to 9 pm during summer months and easy access using the tram system, boosted the popularity of the pool.

For the Transvaal Amateur Swimming Association (TASA) the bath met all its requirements for a swimming tournament. Hence it applied to hold the Currie Cup33 (swimming tournament) on February 1910. The town council duly approved the application, provided the TASA paid the council 7½ percent of the total receipts from the sale of tickets.

It was soon apparent that the facilities provided in 1909 were inadequate. Minor additional facilities were added during the 1910s. In 1912 a stand to accommodate 800 spectators was erected at the north side of the park. It was seen as an important addition and welcomed "as a boon to the public … who throng to the baths as sightseers on Saturdays and Sundays …". It also served as a shelter for the swimming bath against dust during the dust storm season. Ellis Park was gradually getting the trimmings of a proper sporting venue. The 1920s and 1930s, however, saw more substantial additional developments at the bath, inter alia a three-storeyed building with 98 new dressing booths as well as a tea servery on the lawns.

swimming bath indeed fulfilled the prophecy in the mayor's minute of 1909 that it would prove to be "a distinct boon to the city". Galen Cranz's remark that "swimming pools [in the USA] were more popular than any other single facility", was certainly true in the case of Ellis Park.